A cafeteria plan is a mechanism that offers employees a choice between cash (i.e. their full salary as taxable income) or non-taxable qualified benefits (i.e. allows employees to pay with pre-tax dollars.) All cafeteria plans are salary reduction plans based on Internal Revenue Code §125, however, there are many plan design variations and not all cafeteria plans are the same.

A Premium Only Plan (POP, also sometimes called a Premium Conversion Plan, PCP) is the simplest form of a cafeteria plan under IRS Code §125. It’s a “premium payment plan” and allows for employers to take certain employee paid premiums for insurance benefits pretax. (e.g. group health, dental, vision)

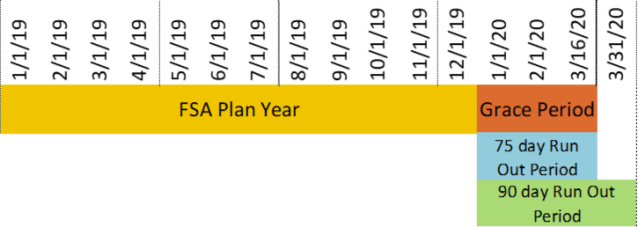

When you have a health and/or dependent care flexible spending account (FSA), that goes beyond the premium payment plan format because you are permitting employees to reduce their salaries before taxes to reimburse medical/childcare expenses.

In addition to the “rules” under IRS Code §125 found in a POP plan, FSAs are subject to special requirements contained in other IRS regulations.

Health FSAs are subject to requirements under Code §105 (self-insured medical reimbursement plans) Code §106 (the requirements for accident and health plans) and Code §125.

Dependent Care FSAs are subject to requirements under Code §129 (“Dependent care assistance programs”) and various special FSA requirements in Code §125 and IRS regulations.

Therefore you need a more complex cafeteria plan document (often called a flexible spending plan) than a POP document to be in compliance when offering an FSA.

The most complex form of a cafeteria plan, sometimes referred to as a “full flex” plan is where an employer provides employees “flex credits” to “spend” on qualified benefits. Depending on the plan design, the employee may be eligible to receive in cash, taxable compensation if the employee doesn’t “spend” all of his flex credits on benefits.

One requirement that every cafeteria plan must meet, is having a written plan document that includes all content specified in the IRS code. e.g. participation rules, election and election change procedures, manner of contributions, etc.

While it is permissible to have separate cafeteria plan documents. i.e. a POP plan document for the insurance premiums and a separate cafeteria plan document for an FSA, for ease of administration most will include a POP component with in their flexible spending plan document.

According to the 2007 proposed cafeteria plan regulations (Treas. Reg. §1.125-1(c)(6))

(6) Failure to satisfy written plan requirements. If there is no written cafeteria plan, or if the written plan fails to satisfy any of the requirements in this paragraph (c) (including cross-referenced requirements), the plan is not a cafeteria plan and an employee’s election between taxable and nontaxable benefits results in gross income to the employee.

In simple terms, failure to have a written plan document employees would be treated as if they had a taxable benefit (e.g wages) even though they received a nontaxable benefit (e.g. health insurance).

The cafeteria plan document is what allows pretax salary reductions and contains the rules the IRS permits. It’s an important document to have and to understand.

The legal issues that arise for staffing firms (e.g. employment agencies, employee leasing organizations) or employers using staffing firms come down to answering these questions:

The legal issues that arise for staffing firms (e.g. employment agencies, employee leasing organizations) or employers using staffing firms come down to answering these questions: